Marianne Trent speaks to Helen Garlick, lawyer turned author, 63, about the shocking confession letter she found after her mother had died.

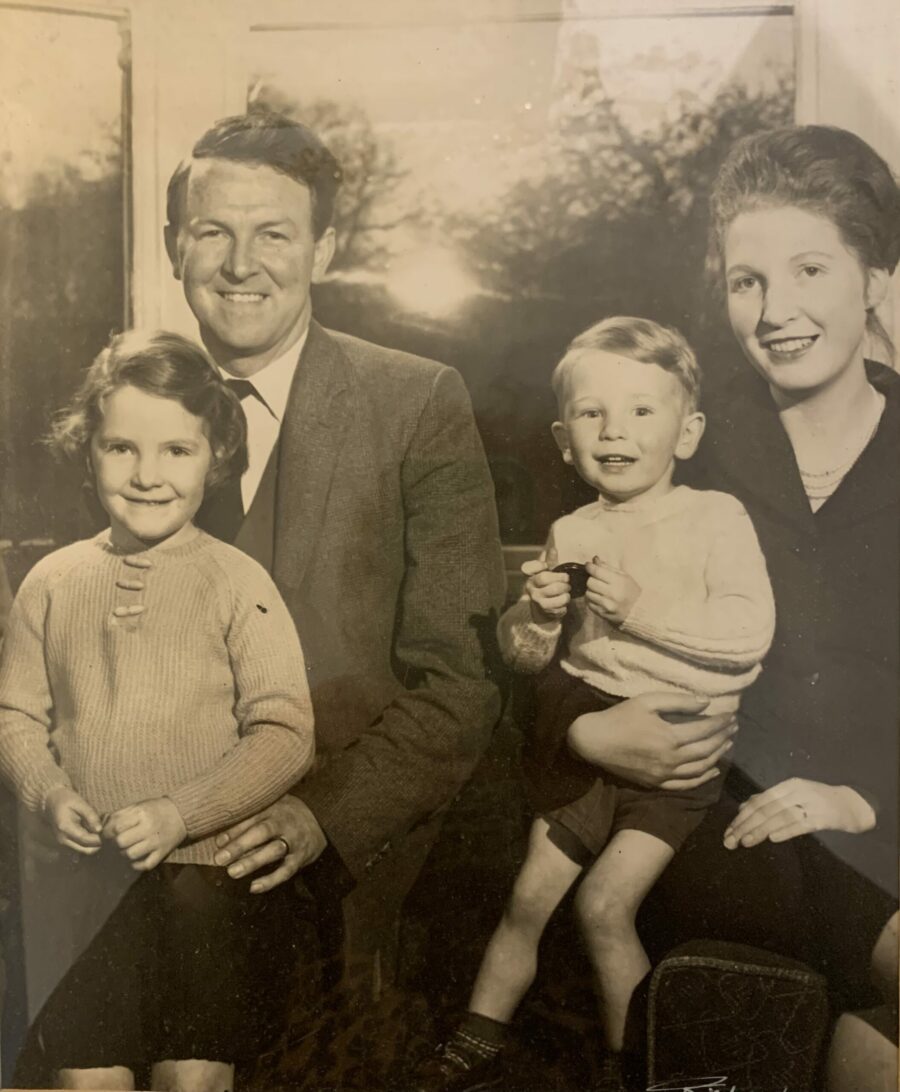

From left to right: Helen, her father, her brother and mother, Monica.

I turned the crumpled envelope over in my hands, covered in familiar handwriting. A single phrase jumped out: “I wonder how other lesbians cope?”. My breath caught in my throat. Why was my mother Monica – a devoted wife of 59 years to my father – writing about being in a gay relationship? Ten days earlier, she had died unexpectedly. Sorting through her personal effects had been calming at first – comforting even – and now this shocking discovery.

Christmas 2017 was just around the corner, beyond that my 60th birthday. Over the years, I had enjoyed a close relationship with mum. My brother had died when I was 22, so I’d become accustomed to the responsibilities of being an only child with ageing parents. My three children, Unity (30), Will (28), and Lilly (22), had experienced the attention and affection of a truly devoted grandmother. Aspects of her had been stolen by dementia and yet, hand on heart, I thought I knew pretty much everything there was to know about her; that she had told me all her stories over the years. It turns out I wasn’t the only family member with an untold truth after all…

Why was my mother Monica – a devoted wife of 59 years to my father – writing about being in a gay relationship?

I was brought up in Yorkshire and Cornwall. To the outside world, my family must have looked perfect. Dad was a well-known and outwardly successful Yorkshire solicitor – the respected president of the Yorkshire Union of Law Societies; my mother, a blonde-haired, blue-eyed beauty raising their two children. When my younger brother David died in 1981, my parents both held on to the belief that his death was accidental. I knew it was suicide – a secret I kept out of respect for them, and later explored as a writer only after first dad, and then mum, had passed away.

The truth about mum’s life as a closeted lesbian was so big, so out of left field, that no-one had seen it coming. When we settled her in at a care home in West Wittering ten days earlier, we could not have known she would be dead at the age of 86, just over a week later; could never have guessed that she had left a bombshell confession, which I truly believe she meant for me to find.

Helen Garlick

I had a sense memory of first seeing the envelope when I was packing up mum’s things from her room. I had popped it in the boxes with everything else so I could take it all back to my flat. Now, sifting through her papers on my way out to work, I came across it again. Initially, I was so shocked that I doubted myself. “Does that say ‘lesbians’?” I asked my fiancé Tim. “Yes,” he said.

We both laughed; it was so out of the blue. Due to her dementia diagnosis, I wasn’t even sure it was true. How was it possible that something so powerful, significant and evocative could have been left unsaid and, in doing so, give rise to so many unanswered questions? And if it was true, how come I didn’t see it? There were so many questions going around in my head, I felt in a spin.

“It’s 2017 and in a little village, no one even mentions it”, mum wrote. “I wonder how other lesbians cope? If I’d been asked if I was like this, I’d always laugh, try to laugh it off. God has made me like this. I know there are others and I have had my share of others who were likewise afflicted…”

She went on to name several women that she’d had relationships with. One was a long-time family friend called Gwen. Could it really be true that Gwen had been my mother’s lover?

Telling the family

“Enough secrets,” I thought. Tim and I told my children – her grandchildren – over the phone that evening. You cannot get more open people than Unity, Will and Lilly, but they were as amazed as I was. None of them had ever considered this might be a possibility either, but we all felt the same way: If only mum had felt comfortable to tell us in person herself…

Through his shock and surprise, Will also commented that it was cool to have a gay grannie! All my children still treasure mum for the unique and extraordinary person that she was – sometimes eccentric, but nonetheless a doting grandmother.

My duty of care to inform didn’t end there. I also decided to tell auntie Judy, mum’s younger sister by seven years. She was gob-smacked! Married for nearly six decades – and (apparently) happily so – nobody suspected that my mum was gay; too afraid to admit the truth and be open about her sexuality.

It makes me terribly sad that she thought of herself as being ‘afflicted’. I wish I’d got a chance to discuss all of this with her, but I’ll forever be thankful that I was able to talk it through with another key player in my mum’s story. Gwen survived my mother for a period of six months. I wasn’t sure how best to broach the subject over the phone, so I settled on writing to her. I explained mum had left a note and I would like to talk to her to find out more.

“Helen”, she wrote back, “I’ve been waiting nearly all Monica’s life for you to ask me! Ask any questions you have”. A breakthrough! We shared intense email exchanges where the long-held secrets were uncovered. I’ve published extracts in my memoir No Place to Lie in the hope that, by exposing my vulnerability and sharing the stories of my family’s history, it would encourage others to talk.

It wasn’t just a book for me; it was a mission and the words flowed out of me. I believe that talking really does help in a way that taking pills or alcohol can never truly reach. Humankind is hardwired for connection, indeed for healing after trauma, if we can just take the road of courage to talk. I also believe in the power of humour, and so that runs through everything I do.

Mum’s choice was to keep her gay relationships a secret in her lifetime, but I didn’t want to hold back about David’s death while I am alive, and I want to be able to advocate for others who are experiencing suicidal thoughts. Having talked publicly about the prevalence of suicide, in May 2021, I was proud to be made an ambassador of the Zero Suicide Alliance – a role that gives me a sense of purpose.

With hindsight, I only wish my brother had felt able to talk about his mental health struggles and that my mum had spoken out about her sexuality when she was alive. Open communication would have helped both her and David to express themselves more freely.

As much as I would have loved to have known all aspects of my mother and to have seen her in love, it is a privilege to know my mum more fully now.

Dr Marianne Trent, Clinical Psychologist & Author of The Grief Collective, writes:

I am so pleased that Helen was able to learn such important information about her mum. It’s also wonderful that Gwen was able to fill in some important gaps in the story too.

When things feel like a taboo, it can be difficult to speak out and to be honest with ourselves – let alone others. Over our more recent history, there has been a societal shift towards positive self-expression, self-acceptance and not necessarily conforming to the expectations that previous generations might have felt pressure to obey. This has given people almost transformational permission and power to use latter life stages to have important realisations and, in turn, important conversations.

When secrets emerge within families, there can be a variety of reactions ranging from shock, disbelief, grief and even anger. It can be helpful to give everyone a chance to react and to reflect as a primary response. It might be that everyone needs some time for the dust to settle and for the primary responses to relent. This can be a key chance to then have conversations together in smaller groups or as a whole family. There might be much yearning and trying to fathom and make looser threads feel connected again.

It can be important to remember that if you’re speaking to young children, they have short attention spans and get ‘full up’ quickly. Depending on individual differences within your family, the same might be true of grown-ups too! People might need to take away small snippets to consider one piece at a time and then come back for further questions or sense making. This of course can be confounded when the whole family are responding to news and revelations from the grief, as no one person is the ‘expert’ with all – or even any – of the answers.

If it feels like conversations are taking a turn towards ‘Groundhog Day’, battle lines have been drawn, or stalemate positions have been reached, then it might be a good idea to seek professional help. You can reach out to a family and relationship service such as Relate, or individual qualified clinicians on Psychology Today or Counselling Directory.

Remember that you don’t deserve to suffer and, honestly, connecting to all parts of yourself can be wonderfully liberating. Like Helen discovered, younger generations are often more open and accepting of difference. Through celebrating your individuality, you too might come to regard your differences as a strength – even your crowning glory.